Then the great thing swooped and struck upward: a thousand kilograms of center bulk that swallowed the trussed creature in a single gulp, thirty-meter-long tentacles that reached blindly for more prey, the big eye in the middle mad and livid with malevolence. Past Master, Chapter 6

The three of them were onto the hydra before it thunderously shattered the water as it fell back from its great surge. They went with snake-like knives for the hydra eye and the brain behind it, feverish in their haste before the terrible tentacles could be brought to defend and to attack. Hysterical battle, hooting challenge, high screaming triumph. – Chapter 6

"You ever cook any Devil brains yourself? Don't knock it if you haven't tried it. Paul and the green-robe cooked the brains. They cased them in a ball of mud, and set it into a quickly-started and explosively hot fire of oil-dripping vines." – Chapter 6

Now, I don't know what a dromedary is, I don't know what a sand dune is, and I sure don't know what a Syrian is. The name was hung onto me, I believe, because I have a beak instead of a nose. The world will end again tomorrow. Watch then for a Syrian and a sand dune. – Chapter 13

There would be wild stories, the prodigies, the old wives' tales—such as nine snakes slithering out of the severed head; such as the most beautiful woman of Astrobe going up the scaffold and boldly taking the head in a basket, and being turned into an old woman when she came down with it. – Chapter 13

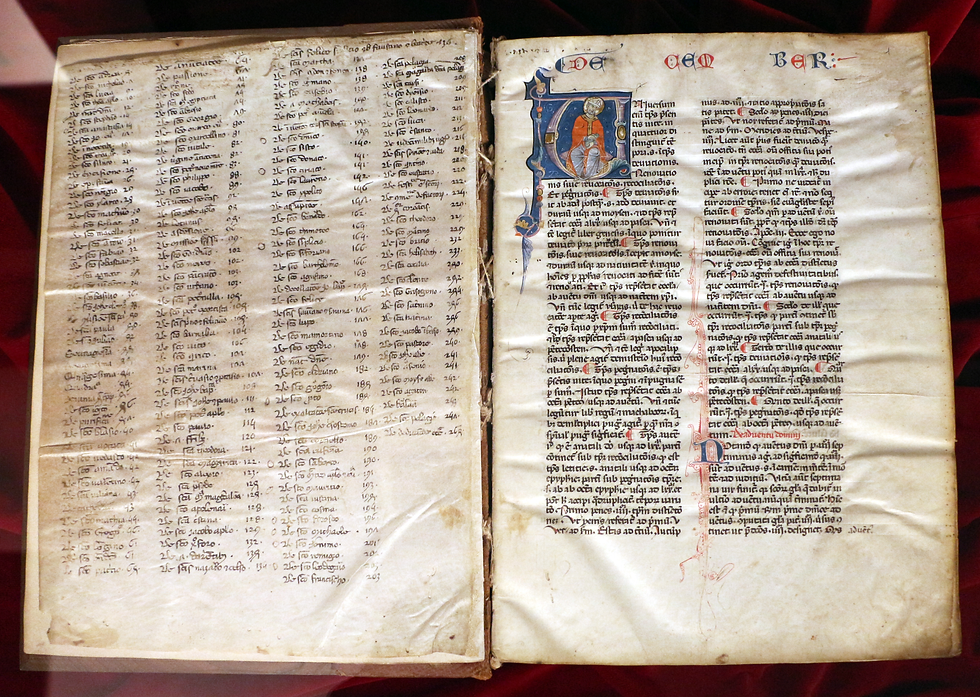

One of the most intriguing details in Past Master is the sudden appearance of George the Syrian in its final chapter. You may have come across The Golden Legend, Jacobus de Voragine’s 13th-century hagiographic compilation, which popularized the tale of St. George and the Dragon, or seen St. George depicted in Christian art.

De Voragine presents George as a knight who saves a city terrorized by a monstrous serpent. According to the legend, the dragon demanded human sacrifices, and when the king's daughter was chosen, George intervened, subduing the beast with the sign of the cross before slaying it. The grateful citizens converted to Christianity.

The dragon that St. George slays is no ordinary beast; it is often interpreted as the great dragon of the Apocalypse, the serpent of Revelation 12:9, "that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world." In the medieval tradition, the slaying of the dragon is the triumph of good over evil, of divine order over chaos. This connection makes George not just a hero of legend but a figure in a larger cosmic struggle, a warrior against the same primordial adversary that appears at the end of time—an appropriate presence in Past Master's apocalyptic ending.

St. George is famed as England’s patron saint, but fewer realize he is also the patron of Syria.. There is even a legendary tradition claiming that he was not born in Cappadocia but in Syria itself.

In St. George of Cappadocia in Legend and History (1909), Cornelia Steketee Hulst wrote:

“In later centuries the combat with the dragon came to be one of the most romantic stories of Europe, and St. George as a romantic hero surpassed the great national heroes such as Cid, Orlando, King Arthur, Ogier the Dane, and Red Beard. Each nation that touched his story left its mark upon it, and most of the nations touched it. Swedish and Danish, German and Norman French ballads and tales of St. George and the Dragon are numerous between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Seven Grecian cities claim the honor of Homer’s birth, but more than seven countries claim the honour of St. George’s birth and struggle with the dragon, some placing it in Cappadocia, some in Libya, others in Syria . . .”

This theme of the legendary slayer appearing at times of upheaval recurs throughout Past Master, most memorably in the legend Scrivener’s grandmother tells him. In Chapter 6, the slaying of the devil hydra is another instance of this pattern, foreshadowing the novel’s climax, where the true hydra manipulating Astrobe—the Nine Programmed Persons—is finally brought down.

The novel also presents this idea through George the Syrian, who tells a story about how, after the world ends, there is always a hill, a Syrian, and a camel. Though George ultimately falls—and though he doesn’t know why he has his name, what a Syrian is, or what a dromedary is—the echoes of a world that ended two temporal sequences ago still shape the novel’s present.

St. George, like St. Thomas More, met his end by decapitation. His feast day is coming up on April 23—tip a glass to him.

“The programmed guards got George and Maxwell and Rimrock and added their blood to the transcendental yeast that was beginning to work.”

Comments